Han

Is this idea of mass frustration distinctly Korean, or is it more international in scope? In her ongoing column on untranslatable words, Veronica Esposito looks at han, including how it appears in literature and popular culture—from a fifteenth-century folk song to BTS and Snoop Dogg.

It is common to hear that a word is untranslatable because it is only comprehensible to members of a particular group. Thus toska is said to be uniquely descriptive of the Russian soul, wabi-sabi is evocative of aspects of Japanese culture that only those born there can grasp, and hygge is best understood by a Dane, who knows what it’s like to get though long, bitterly cold winters. As the logic goes, if you’re not part of the nations these words come from, you just can’t get what they mean.

The Korean word han comes across like a turbocharged version of this phenomenon. A South Korean figure skater gives an awe-inspiring Olympic performance but nonetheless only receives the silver medal, and her fans’ frustration is labeled as a mass experience of han. A world-famous Korean poet—the perennial Nobel candidate Ko Un—argues that han is biologically born into Koreans: “We cannot deny that we were born from the womb of han and raised in the bosom of han.” One scholar even professes that han is built up of sufferings comprising the entire five-thousand-year history of the Korean civilization. It is all-encompassing and without peer, perhaps the very basis of Korea’s culture, what makes Koreans unique. Reading through the writing surrounding this concept, it is common to find extremely heightened sentiments like the following, which researcher Sandra So Hee Chi Kim reported as being delivered by an elderly Korean man to an American Korean studies scholar: “I am so happy to hear about an American professor who wants to learn about my country. I can teach you what you need to know. It is a word called han and the soul of Korean art, literature, and film.”

The first thing to know about han is that it is the subject of much disagreement.

So just what is this portentous word? Well, the first thing to know about han is that it is the subject of much disagreement. Just where does this term originate? Some, like scholar Kim Yol-kyu, argue that it represents “the collective trauma and the memories of sufferings imposed upon [the Korean people]” over five thousand years; others, like Sandra So Hee Chi Kim, define it as specifically coming out of Japan’s period of colonization during the twentieth century: “han did not exist in ancient Korea but was an idea anachronistically imposed on Koreans during the Japanese colonial period.” Others, like Minsoo Kang, have even argued that the word has become largely irrelevant to younger generations, claiming that han “is about as useful at explaining everything Korean as the term ‘rugged individualism’ is at explaining everything American or the ‘Samurai’ is in capturing all that is Japanese.”

Regardless of where one believes the word comes from—or of its ongoing relevance—there are points of overlap among most definitions of han: it has to do with resentment, sorrow, and regret, it is expressive of something deeply Korean, and it emerged from the Chinese character han. Some have also found hope in han, claiming that the trials inherent to the concept are also a part of “creating complex beauty.”

The word is associated with deeply rooted parts of Korean culture.

The word is associated with deeply rooted parts of Korean culture. For one thing, it is closely linked with the traditional Korean art form pansori, which typically involves a vocalist and a percussionist and tells epic stories occupying from three to eight hours. According to scholar Heather Willoughby, pansori requires years of intense study to successfully marshal a variety of acoustic and gestural elements in order to create a unique experience of han. Pansori is believed to have originated in the 1600s; as the art form reached its so-called golden age in the 1800s, it was engaged in tragicomic stories that ultimately ended happily—not exactly the stuff of han. But by the twentieth century, pansori had come to focus more and more on the tragic aspects of its narratives, and this is when it began to be the stuff of han, coming to be known as “the sound of han.”

The Korean folk song “Arirang” has also been closely associated with han, with some even calling it the “anthem of han.” Considered to date back to at least the 1400s, the song relates the trials of two lovers who struggle to be together. In 1864 historian and missionary Homer B. Hulbert described “Arirang” as extremely central to Korean culture, saying that it occupied the same place in Korean music as rice does in the Korean diet, and today there are countless versions of the song available for listening. According to scholars Jeongwon Yang and Sun-Hee Lee, “Arirang” took a turn toward han during the Japanese occupation, as it became a focus point of solidarity against colonization. Throughout the twentieth century, the song grew more and more connected with han as both a way to represent suffering and as a means of retaining hope in the face of immense challenges. It is also seen as a common point of reference amid the experience of han in the Korean diaspora.

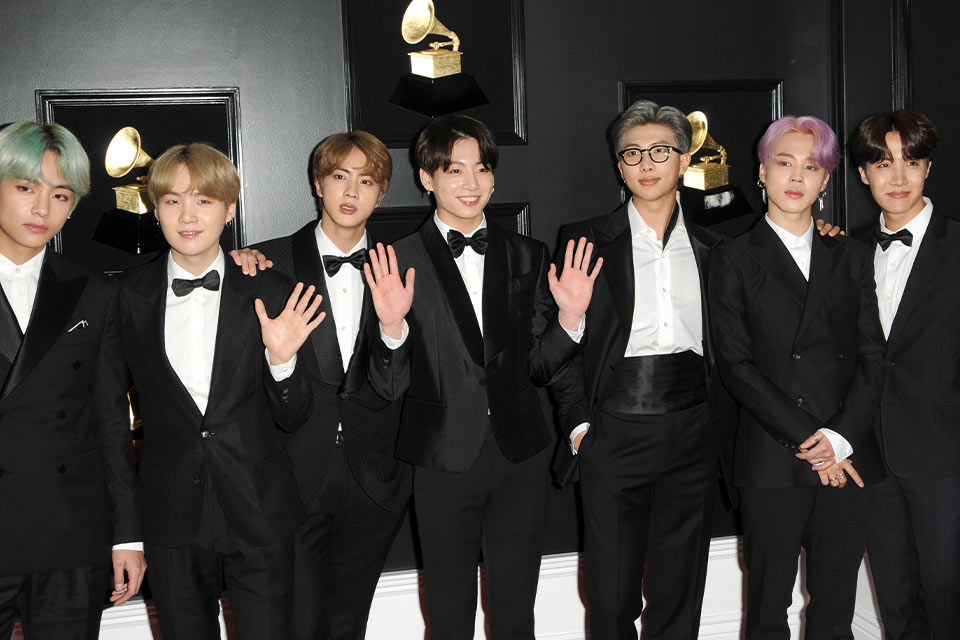

Han has also been considered a part of many of the most globally popular pieces of contemporary Korean culture. For instance, researcher Björn Boman has argued it is the one thing that unites K-pop idols like BTS, Luna, and (G)I-DLE. Boman concludes that “han in the analyzed K-pop contents, while often implicit rather than explicit, expresses lost love, the transgenerational understanding of Korean grief, or an appeal to the collective feeling of vulnerability among global audiences”—in effect, that han continues to be a cultural touchstone in Korea, regardless whether it is being consciously evoked or not.

Likewise with K-lit. Writing in The Guardian, Miriam Balanescu quotes Korean author Frances Cha—whose novel If I Had Your Face delves into the widespread use of plastic surgery to modify the faces of Korean women—as assigning han a distinctly feminist slant: “A lot of women in my life have [han]. Mothers-in-law tend to have it because they were daughters-in-law and were mistreated by their own mothers-in-law. It’s been a very vicious cycle historically.” The concept is also seen in popular Korean writing like Han Kang’s Man Booker International Prize–winning The Vegetarian.

In her essay “Korean ‘Han’ and the Postcolonial Afterlives of ‘The Beauty of Sorrow,’” scholar Sandra So Hee Chi Kim suggests that han has transcended its roots as a purely Korean concept, finding relevance in other cultures and contexts. She challenges the notion of han as an untranslatable word that only true Koreans can understand. Hellena Moon, for example, suggests that han ‘‘is transcultural, intercultural, and extant in all human communities.’’ She claims that it is not the uniqueness of han that makes it untranslatable, but the unique experience of suffering that in and of itself is always untranslatable, and that melancholy marks any colonial and postcolonial context. I would like to suggest that there is truth in both claims. Han is an affect, a habit, a practice, and an imaginary based within the sounds and scripts of colonial and postcolonial historical experience. Such historical experiences are not unique to Korea, and the affect that han analogically indexes is one that is experienced by multiple groups around the world.

Han is an affect, a habit, a practice, and an imaginary based within the sounds and scripts of colonial and postcolonial historical experience.

Kim goes on to read han into various contexts: the work of African American authors like Richard Wright as well as other aspects of the African American experience. She discusses it in the context of musical collaborations between Korean pop stars (Psy, Tablo) and major American rappers (Snoop Dogg, Joey Bada$$). She ultimately concludes that “the term itself is embedded in a specific history that we should not forget. . . . Even though han, let alone race itself, are social constructs, critical han turns a magnifying glass on to the ways in which race and racial difference continue to saturate our material and psychic lives.”

The scholar Elaine Kim provides a stirring example of what Sandra So Hee Chi Kim has described as diasporic han in the Korean American context. In “Home Is Where the Han Is: A Korean American Perspective on the Los Angeles Upheavals,” Kim discusses han in the context of the Korean American experience of the 1992 Los Angeles riots, injecting her own experiences surrounding those events. She explains how, seeing Koreatown sacrificed in the riots, “I had the terrible thought that there would be no belonging and that we were . . . a people destined to carry our han around with us wherever we went in the world.” She also chronicles her experiences writing a personal essay for the popular magazine Newsweek on the Korean American perspective of the riots and getting reams of racist hate mail in response. “I had encountered a part of America’s legacy, the legacy that insists on silencing certain voices and erasing certain presences, even if it means deportation, internment, and outright murder.”

Ultimately, Kim’s essay is the work of a resolute writer who does not feel Korean enough to live in Korea but who also fears that America may not be a home for her either. “What is clear is we cannot ‘become American’ without dying of han unless we think about community in new ways.” She expresses hope that Koreans can create a “new culture of survival and recovery, so that our han might be released and we might be free to dream fiercely of different possibilities.” Perhaps more than anything else, her piece shows the extent to which han does continue to resonate with Koreans, even amid vastly different situations. Her writing affirms that translatability is a concept that exceeds the linguistic sphere—her discussion of han, as well as Sandra So Hee Chi Kim’s, shows the word taking root in new geographic locations, new forms of creativity, and new historical circumstances. It is a word that is at once untranslatable and also translatable.

Oakland, California